GUEST POST

(PHOTO: Len Schneider)

Quick: What’s the most misused term in audio next to “subwoofer”?

You, yeah, you in the back there – did you say “hi-res”?

No more calls, folks, we have a winner!

The Recent Past…

Almost lost in the firestorm of publicity about Dolby Atmos, that company’s new surround sound technology, was an announcement by a consortium of industry organizations that purported to de-confuse the world of high-resolution (“hi-res”) audio.

Long needed, this effort brought heavy hitters from various segments of our industry and resulted in both a definition of high-resolution audio and four categories of this hi-res universe that would – or so it was intended – guide the music industry and component manufacturers in their efforts to promote this supposedly better way to reproduce music. And, yes, the consumer would get a heads-up of what to expect when considering the purchase of a one of these new “hi-res” sources.

The industry organizations include the Digital Entertainment Group (DEG), the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA), the Producers and Engineers Wing of the Recording Academy (the folks who bring you the Grammys), and major record labels such as Sony Music Entertainment, Universal Music Group, and Warner Music Group.

Call in the consortium…

The definition of “hi-res,” took some effort as there was little agreement among these entities at the beginning of the process. And, indeed, the effort was designed more to unify marketing efforts as the consortium recognized at the outset that “hi-res” meant pretty much whatever anyone wanted it to mean.

The definition finally accepted reads, in part, “lossless audio that is capable of reproducing the full range of sound from recordings that have been mastered from better than CD quality music sources.”

Under this broad umbrella, the consortium decreed four categories of “hi-res” sources, all under the somewhat misleading banner of “master quality.” They are:

• MQ-P From a PCM master source 48 kHz/20-bit or higher; (typically 96/24 or 192/24 content)

• MQ-A From an analog master source

• MQ-C From a CD master source (44.1 kHz/16 bit content)

• MQ-D From a DSD/DSF master source (typically 2.8 or 5.6 MHz content)

Heading into the jungle…

At an off-site introduction hosted by NYC’s Jungle City Studios during June’s CE Week, the group brought together several mastering engineers and producers to present some of their recent hi-res efforts. Indeed, the mini-soiree was successful in that many of the attendees heard music that exhibited a rare level of immediacy. Of course, that was to be expected as the luminaries included Grammy Award-winners Chuck Ainsley, Frank Filipetti, and Bob Ludwig among other similarly-accomplished people.

But questions arose, even if voiced privately by some of the more knowledgeable attendees. What “master quality” are we talking about? Is it musical quality? engineering quality? sonic quality?

Behind that, even a casual parsing of the definitions quickly reveals that the consortium was actually defining “provenance” rather than “quality,” thus leaving anyone seeking clarification from these efforts on his or her own when searching for aural Nirvana.

Set the WayBack Machine…

Of course, the grey heads among us had seen this before, hadn’t we? Think back to the early ‘80s (the dawn of consumer-oriented digital) and the SPARS code, an attempt to classify sources (primarily CDs) according to their origins – analog, digital, or some combination thereof. Without going into mind-numbing detail, let’s take a quick look at that early (and now largely ignored) code.

SPARS identified these sources by noting their pathway, if you will, from original recording session to playback using a three-character combination of the letters: “D” (for digital) and “A” (for analog.)

Under the SPARS code, there were many permutations of this seemingly simple system.

• AAA – A fully analog recording, from the original session to mastering. This covered LPs only as it should be obvious that the final letter must be a “D” if the material was released on CD.

• AAD – Analog tape recorders used during initial recording and mixing, followed by digital mastering (post production level matching, EQ, or other processes intended to make the final product more “listenable.”

• ADD – Initial recording on analog tape, followed by mixing and mastering in the digital domain. .

• DDD – Digital from original recording through mastering.

• DAD – Initial recording via digital media followed by analog mixing and mastering followed by re-conversion to digital prior to release as a CD.

• DDA – Begins with a digital recording followed by digital mixing and mastering, but converted to analog for the final release on vinyl.

The Problem With SPARS…

SPARS’s main limitation was that it covered only the recorder but did not account for other equipment used in post-production (EQ devices, limiters, etc.) nor for the fact that some analog material was converted to digital and then back to analog before release. For example, during the mixing stage some recordings marked to indicate digital mixing may have actually been converted from digital to analog, mixed on an analog console, then converted back to digital and digitally re-recorded, thus “earning” it a D as the final character in the SPARS coding system. And the converse was also true. SPARS had no way to indicate that a digital source might have been converted back to analog for only a portion of the post-production process but appeared only after reconversion to digital and then further manipulation in the digital domain. Confusing? Yes. Deceptive? Not intentionally.

SPARS was also potentially misleading in that many people took the three-character series as an indication of quality, DDD (all digital from recording to commercial duplication and distribution) being the best that could be.

But many DDD sources were absolutely abysmal – sometimes even punishing – when played back on a system capable of resolving fine details (or, in today’s parlance, a “high resolution” system) despite the fact that consumers often paid a premium for DDD recordings even when AAD recordings of the same material were available – and often sounded better than their DDD descendants!

Back To The Present . . .Here we go again…

The recently adopted DEG/CEA/Recording Academy classification system is somewhat flawed in a manner similar to the shortcomings of SPARS. Yes, it identifies the origin of whatever is being promoted as “hi-res” but, like SPARS, it is a voluntary system that music producers are not obligated to follow. And, as pointed out earlier, it carries little or no assurance of audible quality.

That’s our main complaint about this new effort. In a Facebook conversation that was prompted by this writer’s contention that “quality” and “provenance” were definitely not the same, I was chided by one of the people involved in the process not to “sacrifice the good on the altar of the perfect.” In other words, the new classification system can be said to remind one of the old shibboleth “good enough for government work” (and the negatives that phrase usually implies). And one might not be far from wrong in so doing.

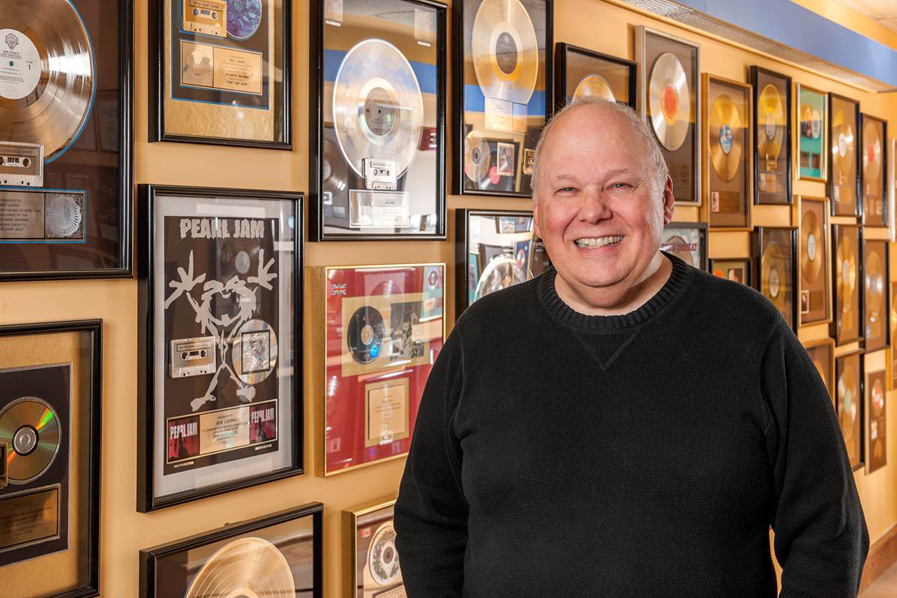

In an effort to avoid a descent into minutiae, this writer traveled to Portland, Maine to talk with Bob Ludwig, a mastering engineer par excellence, a person whose accomplishments in preparing more gold, platinum, and Grammy winning music arguably exceed those of most competent people in that demanding confluence of science and art. The fact that he has a bachelor and a master’s degree in music gives him the sensibility that augments his technical expertise.

(PHOTO: Peter Luehr, used with permission)

Gateway Mastering…

Gateway Mastering Studios, Inc., Ludwig’s home base, occupies two floors in a mixed use building close to Portland’s increasingly cosmopolitan heart. Chosen more than 20 years ago as a more conducive environment than midtown Manhattan, the studio is surprisingly simple on first look but is literally packed with the tools of the mastering trade. The ground floor studio is “my room” according to Ludwig but is supplemented by other mixing rooms, one devoted exclusively to surround sources and, in an ongoing acknowledgement of the changing nature of the music business, a separate server room to assure near-instantaneous communications with musicians, producers, and engineers throughout the world.

The ensuing conversation was wide-ranging and reflected Ludwig’s virtually panoramic perspective on both musical aesthetics and the engineering challenges in bringing hi-res audio to music aficionados. As the conversation delved more deeply into substantive issues, the more obvious it became that any system predicated on easily defined categories, however well-intentioned, could never act as a definitive guide to what our ears perceive.

Music industry budget woes…

Ludwig first shared information on the format – analog or digital – in which most projects arrive at Gateway Mastering. “Budget woes in the music business,” he began, “have meant that almost everything coming in to me is in a digital format. In fact, the only 100% analog project so far this year is Jack White’s Lazaretto.”

And the essential sonic difference between analog and digital? “Analog has fewer transients, is smoother, but not as accurate. Hi-res digital sources,” he assumes, “are more accurate but there’s an aesthetic choice here, too.” The implication, obviously, is that personal taste can be a major factor in choosing one or the other.

As an indication of the difficulty of picking one or the other, Ludwig explained “I can make a digital copy of a master that you could never reliably pick out which was master and which was a copy. However, I could never make an analog copy of a digital master that you couldn’t pick out!”

Consider The Source…

And there’s another problem. “Most of the projects that come here from recording studios are reasonably good. But a larger and larger percentage of work arrives from independent producers. Here, Pro Tools projects predominate.” (Pro Tools, for those who are not familiar with the program, is the prominent production platform for pop music.) Ludwig identified problems with overall sound quality.

“Today, the average sound that comes into me is the worst in my career and usually contains high distortion levels in addition to overused compression,” Ludwig said.

(PHOTO: Len Schneider)

When asked if this ”sweet spot” was a measurable quantity, Ludwig said “No. That changes from project to project. Some mixes are designed for loud playback, some for lower-level playback. Others where dynamic range is critical – classical music for example – I rarely use any compression at all. Jazz is somewhere in between those extremes.”

Streaming screaming meemies…

He then pointed to iTunes Radio (specifically iTunes’ “Sound Check” system) and other streaming sources such as Pandora that use judicious amounts of leveling to insure listenability without incurring the sonic penalty of extreme compression. “These algorithms are very good,” he stated, “for smoothing out the overall cut-to-cut level differences without affecting the dynamic range of the individual cuts themselves.”

He continued, “But don’t look to these algorithms to reduce distortion in overly compressed cuts. Tracks with little or no compression sound much better in comparison with those suffering from over-compression.”

Ludwig again visited the so-called “loudness wars,” pointing out that, even in Edison’s day, differently shaped needles were used in the quest for more gain. “This continued for some time,” he mentioned, “and some Enoch Light records were so cut so ‘hot’ than even the better phono cartridges of the day couldn’t track them.”

Excessive loudness in digital and analog are different animals, he explained. “Peaks in the analog domain are far more gradual in that they overload the system more gently. Similar peaks in digital, those that exceed ‘digital 0,’ are simply clipped as the digital system runs out of calculating room to deal with them and the result is exceptionally high distortion.”

The weakest link…

One of Ludwig’s major positions is that hi-res audio demands a good playback system. “That trumps everything,” he says, “and it can be anything from a good D/A converter feeding a pair of high quality headphones to a full-blown high fidelity system in a treated room.”

“The format is secondary,” he stated, “Just listen to a disc played on one of the early DVD-A players and then compare it to the same disc played through a Vivaldi D/A, for example. Both may be 24-bit/192 kHz capable but one sounds far better than the other.”

“The playback system is only as good as its weakest link,” Ludwig stated, “and I found that I simply didn’t want to listen to music through one of these early DVD-A players.” However, in responding to a further question, he stated “a 24-bit/192 kHz source played through a DVD-A player was better than 16-bit/44.1kHz source in the same machine.”

(PHOTO: Len Schneider)

Is high-res worth it?…

And so the question remains “Is a hi-res source worth the cost difference in a moderately priced playback system?” The implied answer is “Most likely not.”

When asked directly if the recently promulgated “hi-res” classifications served a real purpose from the aural point of view, Ludwig responded, ”Provenance of some recordings is far more complicated than is allowable in four different classifications.”

He used several examples to illustrate his point. “If you are mixing a recording through an analog desk (Neve, SSL, etc.), there’s no question that the output of that console will be better reflected by high-resolution digital than by low resolution digital.”

“However, you should know that up until recently, one of the five greatest pop and rock mixers in the world transferred everything a producer sent to him onto a 48kHz/20-bit Sony DASH tape machine to use with his console. So everything was brick-walled at 22k or 24k at the source, then the analog output of the desk was mixed at 96k because, legitimately, the output of the analog console would be better reflected by high-resolution digital. But the original recording was still brick-walled at 22 or 24k.”

So what’s your designation?…

So, are the final products from this mastering engineer’s studio considered MQ-P, MQ-A, or MQ-C? Think about it – the answer does not quickly spring to mind.

Further exploration brought the name Astell and Kern into focus. This company’s new flagship AK240, a high quality portable D/A handles all hi-res sources including native DSD64 and DSD128 files without resorting to PCM processing as is often the case with so-called “DSD compatible” units. Ludwig credits “excellent DACs and a solid power supply” for the unit’s ability to easily delineate the difference between conventional and hi-res sample rates. He considers it the go-to answer for critical headphone listening.

We asked a further question: “If an original recording is very high quality, is mastering always done at 192k @ 24 bit?”

Ludwig answered succinctly. “No. For instance, I’ll be doing a Steve Reich project (contemporary classical perhaps verging toward avant-garde), produced by Judy Sherman and probably engineered by John Kilgore, whose work for artists ranging from Big Mama Thornton to Broadway musicals is world-class. Most likely, nothing much will need to be done so if it comes in at 96/24, there’s no need to upsample to 192 and possibly alter the sound.”

Up the downsample?…Or down the upsample?…

Next, we asked, “If you got a source recorded at 192/24, and processed it to your satisfaction in that format but then downsampled to 44.1/16, would the differences in sound quality be audible in that CD version?

His answer, once again, revealed the difficulties in assigning an “MQ-?“ code to a release. “Yes. Most likely, it would be superior than if the producer had “time on his hands” to record simultaneously at 192 & 44.1 and edited both. In that case, the 192 recording downsampled to 44.1 might well sound better.”

”The general rule of thumb,” he continued, “Is that when doing any post-production work at all – which is usually the case – it’s always better to do that with wider bit depth and a higher sampling rate so that any calculations can be done to a finer degree of accuracy and precision. For example, 32 bit “floating point” theoretically provides 1500 dB of dynamic range.”

Whither the dither…

There’s another advantage in high-bit/high sampling rate processing – it revolves around the question of “dither” or white noise added to a digital recording to lower distortion of low amplitude signals. “You want to add dither only once,” said Ludwig, “and processing a 16-bit/44.1K signal means you have to add dither whenever you change anything – level, reverb, EQ, etc. If you’re working with a 24-bit/96K or 192K data stream, you have to add dither only when you downsample the final product to the Red Book CD standard of 16-bit/44.1K – or not at all if you’re mastering a release that will appear on a high-resolution website like HDTracks.”

“What exactly does dither do?” we asked. “It prevents the last bit – the Least Significant Bit or LSB – from toggling on and off. Dither keeps that last bit on all the time and vastly, as in vastly, decreases distortion. Dither is one of the major differences between early digital recordings and more contemporary technology. It’s based on work by Soundstream’s Tom Stockham and work by Canadians Stanley Lipschitz and John Vanderkooy.”

It all depends…

Indeed, Ludwig is very familiar with these early efforts as he mastered the first “hi-res” project (Michael Jonasz’s “Soul Music Airline”) in 1996 at 24-bit/88.2K. Even then, Ludwig was quoted in Billboard as saying “high resolution digital sound is vastly superior to CD-quality audio.”

Ludwig noted that he had done a Beck reissue of “Mutation” at 352.8kHz and finally heard a flaw in the analog master, this after listening closely to the album many, many times. He attributed this to the “better impulse response” at 352.8K. It’s truly difficult to argue with that observation.

Ludwig’s last comment was somewhat surprising in light of the thousands of stereo projects he’s worked on. “Well-done surround sound is closer to a live performance than any stereo reproduction can be. A surround recording at 44.1 could sound more like the live performance than a ‘hi-res’ stereo source,“ he said, “It all depends.”

The most important question of all…

OK, what’s the takeaway here? We offer only one.

The technicalities in recording and mastering almost preclude accurate categorization. We note once again that the four tier classification identified at the beginning of this article is definitely NOT a “quality” judgment even though that word figures prominently in the headings.

Indeed, these classifications appear to be more of a marketing tool than a reliable indication of what we might expect sonically. They, after all, tell us just a bit (pun intentional) about the provenance of a recording. In fact, we’re somewhat perplexed by the intended meaning of “master.” Does it mean the original recording or, more likely, the final “ready-for-prime-time” commercial release? This is an important consideration and even more germane now that we’ve just explored some of the complexities of today’s digital audio world.

And the most important question of all is how will this classification system resonates with consumers as they consider spending additional monies for “hi-res?” We’ll just have to wait for that answer. Stay tuned.

GUEST POST – LEN SCHNEIDER

This post was written by our good friend and knowledgeable technologist, Len Schneider, President of TechniCom Corp.

This post was written by our good friend and knowledgeable technologist, Len Schneider, President of TechniCom Corp.

Originally a retail sales professional and then a manufacturer’s representative, Len moved to product development and marketing positions at Onkyo and Marantz among other companies. Sony’s former National Training Manager, he founded TechniCom Corp. as an independent consultant and added his development expertise to several award-winning audio/video components. A Life Member of the Audio Engineering Society, Len has written four books on home entertainment technology.

Len can be reached at: len@technicomcorp.com.

Leave a Reply