GUEST POST

My Take After a Dolby-Controlled Demo of

Both Commercial and Home Atmos Versions

Someone (even Google can’t tell me who) once said “Nothing is new, only rediscovered.”

Someone (even Google can’t tell me who) once said “Nothing is new, only rediscovered.”

Case in point: Dolby Atmos, now being touted as the Next Big Thing in surround sound technology. [See A Deeper Dive into Dolby Atmos and Atmos Attacks at CE Week] The two most definable points that are said to differentiate Atmos from earlier surround formats (height information and “sound objects”) are, in reality, surprisingly mature approaches to multi-dimensional sound reproduction.

But height may not be as important as you (or Dolby) may think…

Height information is an easy to understand concept. It contributes to the ideal “hemisphere of sound” that should envelop us when we experience a movie. But both Dolby and dts have long promoted the additional realism height can add, Dolby ProLogic IIz being arguably the best-known example even if it is an analog-based matrix approach.

But, you might wonder, is height really such an important contributor to aural realism? Maybe not as much as you think or, more to the point, not as much as Dolby would like you to think. (We’ll get to this in a few paragraphs.)

Sound as an object – what a concept!…

Conceptually, “sound objects” are a different matter entirely. In positioning Atmos as an “object based” surround technology, rather than the more familiar and conventional “channel based” system, Dolby is asking us to stretch our comfort zone in a more (and how I despise this overused word!) immersive dimension.

Although similar to elements that have been used in OOPs (object-oriented programs) since SIMULA appeared in the late ‘60s¹, an Atmos “sound object” is more a matter of application than anything else. (Give Dolby some credit here, though: this is the first time to my knowledge that OOPs principles have been effectively applied to audio.)

New? Or rediscovered?…

So, if height and sound objects aren’t new, what is? Well, how about the scale of the PR effort Dolby is putting behind Atmos? It’s as if the proverbial 800-pound gorilla we all know and (sorta) love finally woke up and began shaking the banana trees.

Indeed, Dolby’s talking point litany has appeared in almost every web- or print-based media outlet that knows what a volume control is – and even in some that don’t.

Although that litany is easy to remember (and, maybe more to the point, easy for a sales person to use while pitching a new A/V processor, additional speakers, and more amplifier channels), a full understanding of “sound object” is surprisingly difficult to come by.

Breathing the atmosphere…

In deference to that age-old parental cry “Eat your vegetables or you won’t get any dessert!,” let’s begin with sound objects.

In the Atmos universe, sound objects are elements of the supporting soundfield conceived by a film’s director and cinema sound engineer(s) as they develop the aural underpinnings of a movie. These elements? Dialogue of course. Music. Sound effects ranging from the cataclysmic to the barely discernible. Or whatever else might emerge from the speakers to disturb someone trying to get some sleep in a darkened cinema or living room.

Sound objects can be static (restricted to one apparent point of origin) or dynamic (moving from one place in the soundfield to another.) Regardless of whether they are static or dynamic, sound objects are individually definable – they’re specific elements of the soundfield.

Of elements and beds…

If sound objects are individual elements, “beds” are more diffuse, less likely to be limited to any precisely defined space, less “localizable,” if you will. Beds, then, display some characteristics that make them more suitable for channel-based rather than object-based systems.

The point is that sound elements and beds are treated differently during playback. Specific sound elements originate (or appeared to originate) from one specific position in that three-dimensional hemisphere. Beds might emerge from “somewhere back there” or “off to the side.” Diffuse, remember? Depending on many factors, principally the director’s vision as implemented by the mixers, many speakers may receive exactly the same information. Or not. It all depends.

Most soundtracks contain both sound objects and beds. In its theatrical implementation, Atmos allows up to 128 separate tracks to be mixed into the Atmos soundtrack as either objects or beds. Again speaking theatrically, an Atmos processor (or “renderer,” as it’s called) can direct the constituent elements of that soundtrack to as many as 64 speakers, each being fed optimized information keyed to that speaker’s exact location in the theater. Of course, the renderer has to be told where these speakers are and what they’re capable of during an Atmos theatrical installation. And you’ll have to program your home Atmos-enabled processor with similar if less detailed information.

The metadata mystery…

How does Atmos achieve this precision? Through the use of metadata, of course!

Defined as “data about the data,” metadata puts a handle on the audio information itself that an engineer can manipulate to position a sound object anywhere in that ideal three-dimensional hemisphere. Metadata, then, tells the Atmos renderer where in the soundfield a sound object will appear, how long it will be there, and, if the object moves, where it will move to, how fast it will move, even describe exactly how that sound object’s pitch will shift as it moves from one spot in the illusion to another.

And don’t forget that metadata is just not passively keyed to the sound objects. Rather, it’s dynamically affected by playback system configuration programmed into the renderer. How many speakers? Where are they? What are their characteristics – frequency response and maximum output level, to name but two – and how would they affect sound quality?

Each and every audience…

All this, incidentally, is done “on the fly” by microprocessors operating under algorithms based on the human hearing mechanism. The goal is to give each audience the same aural perspective the film’s creators had when they designed the soundtrack in the first place. Notice that we said “each audience.” We should have said “each and every audience regardless of the space in which they’re watching the film.

To accomplish this, an Atmos renderer must direct sound objects and beds in a slightly different manner than it would if used in a different screening room or if you moved your Atmos AVR from one home system to another. (Of course it will – that’s why Atmos theatrical installations include individual programming and why you have to go through a setup menu at home.)

Hit or miss…

This is one of the chief advantages of an object-based system as opposed to a channel-based system. The latter are maniacally focused on sending exactly the same signal to exactly the same speakers without much consideration for speaker placement or capability. An object-based system, on the other hand, can present an optimized mix of sound objects and beds regardless of the playback system’s speaker complement.

In the past, placing these aural clues to accurately reproduce creative intentions regardless of the cinema or home playback system was somewhat hit-or-miss. (In this case, cinemas were usually – and I emphasize usually – better than most home systems.)

Sure, we had right, left, and center channel front speakers, right and left surround speakers, occasionally right and left side speakers, and the inevitable (and inevitably misbalanced) subwoofer. A few of us even had height speakers before but they were never serious contenders for a consumer’s attention. “Nah,” they said, “enough already!”

As you can imagine, these calculations are beyond the capability of your average smart phone.

Scaling the heights (Or falling from them)…

Although height information is touted as one of Atmos’ prime benefits, it may not be as important as it first appears to be. Evolutionary biology gives us a clue here.

Due to the fact that man is primarily an earth-bound critter, our senses are more attuned to the horizontal (side-to-side) than to the vertical (up-and-down.)

The very shape of our ears – especially the pinna – suggests very strongly that audio information “from above” was never critical to our development as a species and thus we are simply not as sensitive to information coming from above as we are to lateral audio cues. Extensive psychoacoustic research supports this position.

Then how do you reconcile this biological fact with the fact that height information is so prominently promoted as Atmos’ chief advantage compared to conventional channel-based systems? That’s difficult to answer completely. (Dolby seems not to have addressed this question at all – at least not in publications easily available to the public.)

The implications for both home theater and cinema systems are significant.

Looking for differentiation…

Declining movie attendance gives some reason to believe that theater owners will welcome something that differentiates an experience in their venues from whatever a person may experience at home.

And consumer electronics manufacturers have never shied away from any technology that promises increased sales while providing little or no real consumer benefit. (Want proof of this somewhat pessimistic viewpoint? Look at 3D TV – if you can find one.)

Both situations ask the question “If we’re not as sensitive to it, is height information all that important?” Well, it may contribute a bit of additional realism but the practical limitations and the expense of introducing a sense of height – particularly in the home – may well overwhelm the (comparatively) small aural advantages. From some viewpoints, this seems to be another version of the age-old question: “Is height one of those theoretical attributes that falls victim to the Law of Diminishing Returns?”

The answer? Of course, each theatrical attendee or home viewer has to judge the technology’s effectiveness for him or herself. Based on an admittedly short exposure to both theatrical and home Atmos, this writer is not convinced that the benefit is substantial enough to warrant Atmos-dictated expense, installation headaches, or the additional clutter. Perhaps a salt shaker and a warning not to drink the proffered Kool Aid is appropriate here? The Biblical admonition “Judge not lest ye be judged” definitely does NOT apply as Atmos deserves your most critical (read “most objective”) evaluation. The problem after all is said and done is that it’s still a value judgment.

But it shouldn’t be a judgment that ignores the fact that Atmos attempts to create a three-dimensional surround soundfield and that height is certainly one of those dimensions.

With that paradox in mind, let’s look at the migration from theater to home.

From the commercial theater to the home theater…

First used for the soundtrack of Pixar’s 2012 movie Brave, Atmos has experienced significant commercial success. According to Dolby, more than 600 screens (surprisingly, most of them NOT in North America) are now outfitted for Atmos sound and 180+ films now sport Atmos soundtracks.

For the consumer electronics industry, however, that’s almost secondary. What we need to understand is how this technology segues into the home.

Let’s begin with a look at some important differences between theatrical and home versions of Atmos.

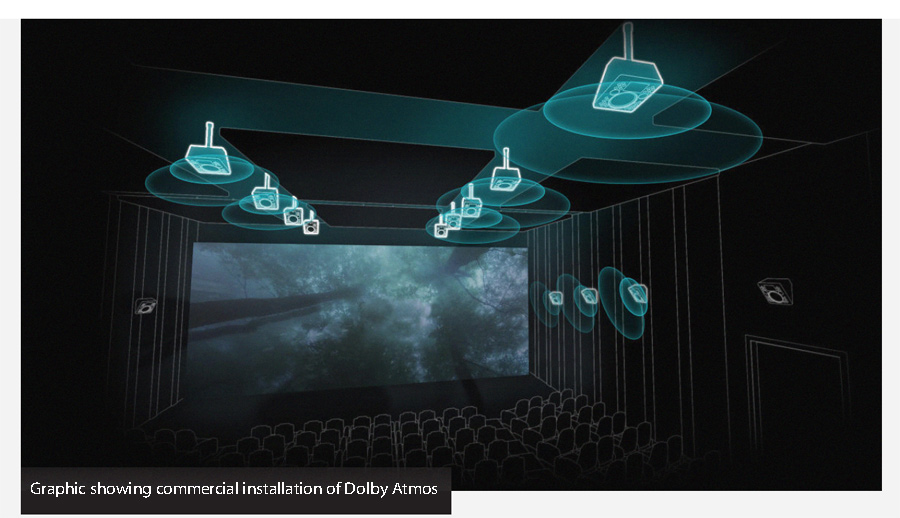

A theatrical Atmos decoder (oops, renderer) supports up to 64 separate speaker outputs. If the theater wants to go full tilt, that means an Atmos renderer, 64 speakers, 64 amplifier channels, money for cabling, installation, calibration, etc. And let’s not forget the safety codes that apply to ceiling mounted speakers in commercial spaces – that alone can entail a substantial expenditure.

A matter of degree…

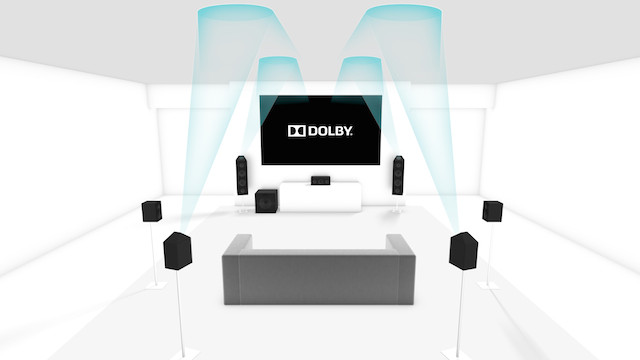

In contrast, a domestic Atmos renderer supports a maximum of 34 speakers, 24 at or just below seated ear level and 10 reserved for height information (either ceiling mounted, Atmos-enabled floor-standers, or Atmos-optimized add-ons.) Lest you think that’s small change by theatrical standards, 24 speakers spaced and aimed properly means that you’ll have a speaker at every 15º increment around the main listening/viewing position. Let’s revisit that: Every 15º! (This may be important in the same universe that produces unobtanium but it has almost no value whatsoever in the real world – or at least not in this writer’s real world.)

A theatrical Atmos renderer can provide two levels of equalization for each of those 64 speakers. Although details for home systems are far less complete, there is no mention of equalization (other than bass management) in Dolby’s home-oriented white paper. No further comment possible here. Is this a demerit for home Atmos? Who knows.

Enough with the theory already!…

Assuming that some readers have already experienced their eyes going plaid from all this, let’s take a quick journey in time back to August 13, when Dolby hosted a herd of press people at their East Coast Atmos-fest at the company’s offices and screening rooms in Manhattan.

Assuming that some readers have already experienced their eyes going plaid from all this, let’s take a quick journey in time back to August 13, when Dolby hosted a herd of press people at their East Coast Atmos-fest at the company’s offices and screening rooms in Manhattan.

The agenda was multi-faceted. We were split into groups to make individual presentations more personal and intimate, hopefully more meaningful. We heard Atmos in the main theater, we hear Atmos in a much smaller home-like setting in an upstairs office, we heard Atmos over headphones (yes, headphones!), and we had an opportunity to barrage Brett Crockett, Dolby’s sound technology research guru, with some pertinent questions. (Well, we thought they were pertinent!) What we didn’t get to do was sit in the big Q&A session with Craig Eggers, Dolby’s chief link between the company itself and the consumer electronics community. This resulted from a scheduling glitch that wasn’t discovered until after that session was over and Eggers had “left the building.”

Nonetheless, what we heard in the other sessions was instructive. Without going into endless details, I’ll highlight the impressions that stayed with me – hopefully the important ones.

I didn’t duck…

First, Atmos in the Dolby-calibrated theater was impressive but more for the clarity of the soundtrack than for the contribution that height information provided. The cinema clip, a fairly long segment of Star Trek Into Darkness, was well received, indeed very well mixed and clear. We were told that we might experience an involuntary reflex to duck during a scene where spears were thrown at the principals. Yes, I heard the spear zipping from front to rear. (No, I did not duck.)

It would have been far more revelatory if we had had the opportunity to revisit that clip with the Atmos soundtrack and then with a conventional 7.1 version. Time, unfortunately, didn’t allow that.

Listening to Atmos in headphones…

A short session with a not-quite-ready-for-prime-time version of Atmos optimized for portable use (games, etc.) was really impressive, however – perhaps the most spatially enjoyable and involving experience I’ve ever had with headphones. (Unmodified Sennheisers, by the way.) Impressive. I wanted more.

Perhaps the most anticipated portion of the afternoon was the time we spent in the faux home environment in an office. And, at least to my ears, one of the least revelatory. Although I suspect most of the press shared this impression, I was not able to hear any significant difference between a clip using ceiling-mounted speakers and a second pass using Atmos-enabled floor standing speakers. I was not prepared for this as I “knew” going in that the ceiling speakers were superior. So much for my preconceptions.

One thing I did hear, however, was a substantial difference as our hosts played an audio track of a helicopter circling “above” us. Frankly, the height component, while there, wasn’t as impressive as was the sense of far better integration, if you will, as the sound of the circling helicopter moved from speaker to speaker. With the full Armos array, those transitions were very smooth. With the conventional (non-height) array, the helicopter seemed to “snap” or jerk from speaker to speaker. The transitions were more than a bit disturbing but, again, there wasn’t time to do the extended listening that might point to why I heard what I think I heard.

The takeaway…

Although Atmos technology is fascinating, I have to reserve judgment on its importance. At the present, I am disinclined to believe that height itself is a major aural advantage although I’m certainly ready to revisit this. I am perplexed by the lingering contradiction pointed out earlier – Atmos-rendered tracks did sound better than non-Atmos versions of the same material. But not by much and I still don’t accept the claim that height information alone is the reason. At least it wasn’t my conscious perception of height as another element of the soundfield.

Of course, someone is bound to point out that you can’t have a hemisphere of sound without height. But I don’t think that’s the whole magilla. In any case, I need far more time and extended listening sessions before the jury of my ears reaches a verdict.

FOOTNOTE

¹ C++ and Java are contemporary examples of OOPs.

GUEST POST – LEN SCHNEIDER

This post was written by our good friend and knowledgeable technologist, Len Schneider, President of TechniCom Corp.

This post was written by our good friend and knowledgeable technologist, Len Schneider, President of TechniCom Corp.

Originally a retail sales professional and then a manufacturer’s representative, Len moved to product development and marketing positions at Onkyo and Marantz among other companies. Sony’s former National Training Manager, he founded TechniCom Corp. as an independent consultant and added his development expertise to several award-winning audio/video components. A Life Member of the Audio Engineering Society, Len has written four books on home entertainment technology.

Len can be reached at: len@technicomcorp.com.

Leave a Reply