[Photo: By Laitche – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3244373}

Part 1 – A Bill Leebens Guest Post

STRATA-GEE: For some time now, I have been hearing rumbles throughout the audio community, particularly the high-end audio community, about controversy surrounding MQA (Master Quality Authentication) – a U.K. company that claims to have created a proprietary technology that allows for the delivery of “better than lossless” audio via certain streaming services. At first, it seemed like the Holy Grail of audio – delivering music that is identical to the original master recording into your earbuds via streaming services such as Tidal. Then the whispers started – “It sounds like it is too good to be true because it IS too good to be true.“

Recently, a YouTube video appeared that blew the doors of MQA dissent wide open and seems to show that MQA technology is NOT doing what the company claims and leaves many to conclude that MQA is little more than a thinly veiled marketing scam. The company pushed back…hard. I asked Bill Leebens to investigate the swirling whirlwind of controversy now engulfing MQA.

See more on our investigation into MQA…

Innovation is hard. It’s like that old saying that pioneers are the ones with the arrows in their back. Human beings tend to resist change and innovators are often stuck with having to defend their inventions over and over again. This appears to be the case with MQA who enjoyed wide acceptance at the initial launch of their technology with audiences oohing and ahhhhing in early demos. But now forces are pushing back – suggesting that after some independent testing, the technology does not do what the company claims it does.

This is the first of what will be a multi-part investigation into MQA by Strata-gee in conjunction with serial guest-poster Bill Leebens. In an investigation that has spanned a few weeks now, we look at MQA from multiple perspectives with the goal that our reporting will help take Strata-gee readers to the core of the MQA controversy.

MQA Controversy

A True Audio Breakthrough? Or a Marketing Scam?

MQA digital encoding, since its introduction in 2014, has been the subject of more speculation, adulation, and acrimony than almost any single topic in the audio world. Much of that may be due to lofty claims made for exactly what Master Quality Authenticated is and does—but the debate regarding both the process and the company was recently reignited by a video on YouTube, which called into question the effects of MQA encoding and the company’s methods of operation.

A brief history and explanation of where MQA came from, what MQA is, and what it claims to be, is in order.

Bob Stuart was and is a longtime veteran of the audio industry. Working with industrial designer Allen Boothroyd in the early ‘70s, Stuart designed a futuristic preamplifier and power amplifier for Lecson Audio, and the pair went on to become co-founders of Meridian Audio in 1977. https://www.meridian-audio.com/about-meridian/the-meridian-story/

An Innovative History

The company became known both for striking product designs (winners of many Design Council Awards and recognition worldwide) and as pioneers of digital audio, producing one of the first “audiophile “ CD players and several generations of powered speakers utilizing multiple amplifiers and DSP (digital signal processing).

The company’s Meridian Lossless Packing (MLP), a compression codec that allowed delivery of multichannel PCM audio signals on DVD-A discs, gained widespread acceptance following its introduction in a paper by Stuart, Peter Craven, Michael Gerzon and others, delivered at the 9th Regional Convention of the Audio Engineering Society (AES) in Tokyo, 1999.

Stuart and one or more of his co-authors had previously presented several papers on lossless compression, noise-shaping, psychoacoustics, and related topics. None could be called easy reads for laymen.

‘A Hierarchical Approach to Archiving and Distribution’ – Precursor to MQA

AES was once again the launching pad for another paper by Stuart and Craven, presented at the Society’s 137th Convention in Los Angeles, October, 2014. The title, “A Hierarchical Approach to Archiving and Distribution”, was a daunting introduction to an outline of the basics of the process that would come to be called MQA. You can see this paper by clicking here…

In short: MQA is a method of compressing a digital audio signal to facilitate distribution, streaming, and downloading of music files by utilizing less bandwidth as a result of the compression codec. The process manipulates higher-frequency signals through a series of dithering and noise-shaping steps, which are later “unfolded” in a process the company described as “music origami”. The “Master Quality Authentication” aspect was said to analyze the original digital processing chain of a recording, and then present the music signal in its best light. MQA’s own description of the process can be read here: https://www.mqa.co.uk/newsroom/faqs/what-is-mqa

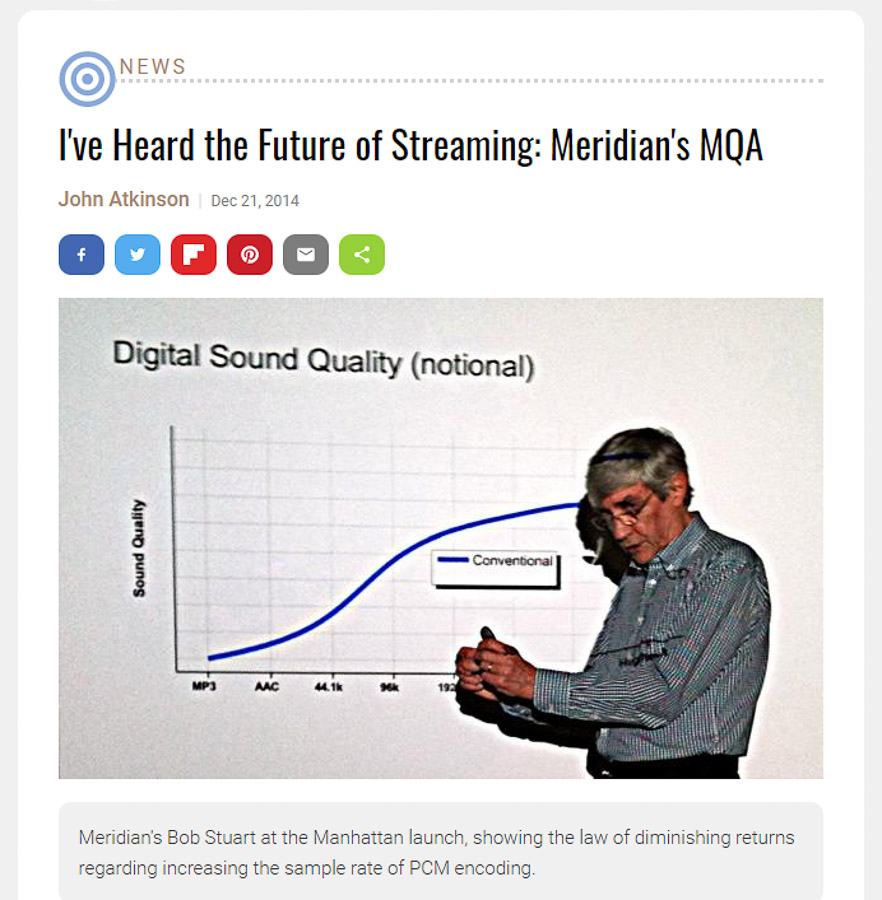

‘I’ve Heard the Future of Streaming: Meridian’s MQA’

Following a December, 2014 demonstration of the process in Meridian’s New York offices, the usually-reserved John Atkinson, longtime Editor of Stereophile, wrote enthusiastically about the demo in a piece headed “I’ve Heard the Future of Streaming: Meridian’s MQA” (perhaps in homage to Jon Landau’s famous statement about Bruce Springsteen). Atkinson wrote, “in almost 40 years of attending audio press events, only rarely have I come away feeling that I was present at the birth of a new world.” He went on to equate the introduction of MQA to the introductions of CD and DSP.

The next month, Meridian conducted a series of demos at CES in Las Vegas. Initial response to the demos was unreservedly enthusiastic; at the time, a well-known recording engineer told me in the halls of the Venetian, “I cried when I heard my masters, they were so beautiful.”

‘Those First Demos Sounded F’ing TERRIFIC’

In the years since, things have become less clear-cut, for a number of reasons (which we will go into in the future). Nonetheless, an audio writer present at the demos recently said, “make no mistake: those first demos sounded f’ing TERRIFIC.” (In spite of the emphatic remark, he declined to be identified.)

In the next installment we’ll look at the media coverage of MQA since the 2015 CES, acceptance and application of the process, views of those in the recording and audio industries regarding MQA (both pro and con), the uproar created by that YouTube video by “GoldenSound”—and what has happened since.

The Wise Words of Marvin the Martian

Keep in mind that few technical fields devolve into abstruse technical jargon as quickly as does the field of digital audio. Even very basic terms are subject to spin, and, shall we say, interpretation. To a layman it may appear to be obsessive niggling over minutiae; to those involved in a field that is, at heart, mathematics—it resembles the pronouncements of Marvin the Martian in an old Looney Tune:

Of course you know: this means war.”

Marvin the Martian (Looney Tunes)

And so, even the fundamental question of, “is MQA lossless?” quickly becomes as muddled as political rhetoric—as we shall soon see.

See more on MQA by visiting: mqa.co.uk.

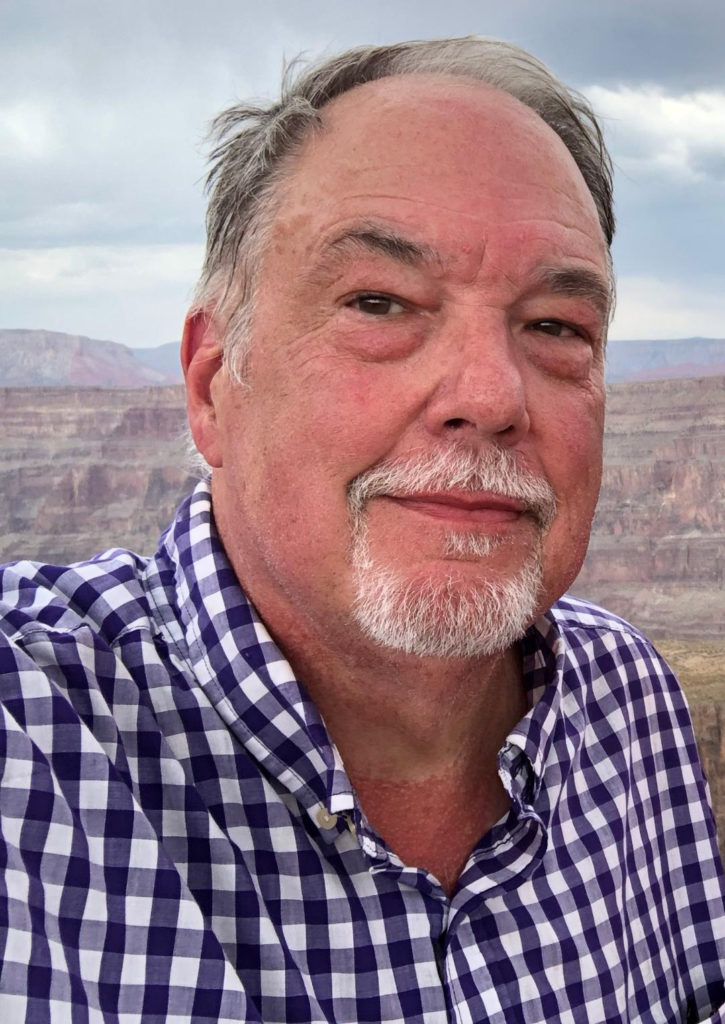

A Bill Leebens Guest Post

Bill Leebens has been a published writer since the age of 15 and has worked in audio since he was 16. He edited Copper magazine while at PS Audio and has also worked in automobile racing, medical imaging, and even as an IRS tax examiner. Bill lives in Colorado with two impatient dogs and several very patient humans.

Reach Bill at: bill@leebensllc.com

I look forward to this analysis. It is a subject that many of us have opinions on, but hard data is far less obvious. Well done for taking the bull by the horns… watch out for the arrows sure to be aimed at your back!

With all the latest high-rez offerings (Apple Music, Amazon HD, Qobuz, etc.) MQA seems to have become a non-issue. Who needs it? Personally, I don’t want all that processing gunk in my signal path. Just give me a pure native high-rez file (FLAC, etc..). Full stop.

Can be FLAC a native high rez file? It is compressed! If producers decide that FLAC is native, why the don’t use it to store the music instead of waiting storage?

FLAC files are losslessly compressed, like ZIP files. They have to be decoded before they can be edited or played, however. Compression is necessary only to reduce storage-capacity or bandwidth requirements, so if you have enough storage or bandwidth available, something like FLAC is just an extra step that you don’t really need. There’s no harm to it, though, even for storing masters.

This is why high end fans only want to go with waf?

Do you mean WAV? Anyhow, take a WAV (PCM) file, convert it to FLAC, then convert it back to WAV (PCM). The decoded file will be exactly the same as the original. That’s what it means for a data stream to be losslessly compressed–what comes out at the end is exactly the same as what went in at the beginning.

Unlike many passionately waged academic controversies the stakes here are not so low. The abstruse nature of the topic leads the lay public to wonder which expert pronouncements are most credible. Debunking “fake science” makes for exciting journalism…if the science is really fake….

I look forward to reading more on this.

Looking forward to discovering how prominent high-end audio individuals went over to the dark side of corrupting fidelity with a witches’ cauldron. Sounds better with mass hifi merchandise because that’s where the shrinking revenue from audio is hanging on. And meantime hoping this mediocre patchwork will attract deep-pocketed tech/computer company to buy the whole mess.

Could be an interesting series. I don’t know much about MQA, but a few preliminary observations:

1) CES demos and the like can be useful or suggestive, but they are never definitive. You don’t really know exactly what is influencing what you hear. In the case of a codec, a proper evaluation would require blind A/B comparison of audio in unencoded (original) versus processed versions. Ideally, even young trained listeners should not detect any difference. This is straightforward for truly lossless codecs such as FLAC, MLP, Dolby TrueHD, or DTS HDMA, but there is a limit to how much bandwidth reduction can be achieved by such means. Going further typically involves applying psychoacoustic modeling to apportion data more efficiently than is possible with lossless compression alone, which is a harder task that yields less certainty. Developing a good lossy codec requires engineering smarts informed by a lot of careful listening comparisons to validate performance and pinpoint problems. The more efficient the codec, the lower the data rate required to achieve acceptable results.

2) MQA is a lossy codec, albeit a novel one in that encoded signals can be played back undecoded with apparently acceptable, if imperfect, sound quality, That’s a benefit of sorts, though not a very compelling one given how cheap it is to decode garden-variety codecs such as MP3, AAC, and AAC+.

3) Lossy codecs in general have gotten a bad rap from audiophiles based partly on the sound of files with excessively restricted data rates but mostly on prejudice. How can removing information not damage the sound? Much too long a story for an already long comment post. The quick rejoinder, however, is that the ear itself does a dramatic amount of data reduction ahead of the auditory nerve. It functions much like the front end of an MP3 encoder, in fact, delivering the brain a smaller amount of reformatted information than what comes off the eardrum. A good lossy codec operated at an adequate data rate can deliver sound quality nearly or entirely indistinguishable by ear from the original.

4) I have occasionally seen claims (which I doubt) that MQA actually improves the sound of recordings. Although I’m not enough a purist to object to something making music sound better, I would want that to be under my control. That is, I should be able to hear the unenhanced original if I choose.

FLAC files are losslessly compressed, like ZIP files. They have to be decoded before they can be edited or played, however. Compression is necessary only to reduce storage-capacity or bandwidth requirements, so if you have enough storage or bandwidth available, something like FLAC is just an extra step that you don’t really need. There’s no harm to it, though, even for storing masters.

There are three things that I will be curious to see as this unfolds:

1. Does it do what it says it does technically?

2. Is the performance improvement measurable?

3. Does the listener perceive a performance improvement that is attributable to MQA or is just from better gear?

Performance improvement relative to what, though? There often seems to be confusion on that point.