Part 3 – Bill Leebens Interviews MQA Founder Bob Stuart & Speaks with Other Supporters Who Remain Loyal

STRATA-GEE: This is the third installment of our series on the controversy engulfing MQA conducted in partnership with guest poster Bill Leebens. You can see Part 1 introduction, MQA Controversy – A True Audio Breakthrough? Or a Marketing Scam?; and Part 2, MQA – Voices Arise in Harmony with a Video Critique from ‘GoldenSound.’ In this post, we hear from proponents of MQA, most of whom remain steadfast in their support for the technology or the company (or both) – even in the face of often blistering criticism. Leebens scored an interview with no less than MQA founder Bob Stuart who calmly answered all of his questions in an interview that lasted more than two hours.

Read the praise from proponents of MQA

To recap: this series was launched in response to a number of queries about MQA, as a result of the recent resurgence in controversy following the release of critical YouTube videos by “GoldenSound” (you can watch the GoldenSound video that kicked off this latest round of controversy in last week’s Part 2 post here). In order to provide a factual, historical framework for the series, in Part 1 we looked into the introduction of MQA, the initial response from media and folks in the audio and recording industries, and a very basic explanation of what it is, and what it does.

Part 2 began with a look at the GoldenSound videos and how that first video seemed to untap a wellspring of bottled-up emotion regarding MQA. From there we looked at other naysayers, the often intensely passionate critics of and opponents to MQA the product and process—and MQA, the company. Casual observers may be bewildered by the unremitting hostility directed towards MQA; referring to a particularly vicious online discussion regarding

MQA, which focused on minutiae understood by few of the commenters and even fewer of the readers, a colleague said, “this whole argument demonstrates the reason this industry will never get bigger (‘this industry” meaning high-end audio). He may have a point.

In this installment we examine the views of the supporters of MQA, those in the audio and recording industries who use the process and like the sound and cite other aspects of the process, including authentication and reduction of file size. On occasion, they criticize the GoldenSound videos—and as was previously noted, finding folks who would comment on the record was not an easy task.

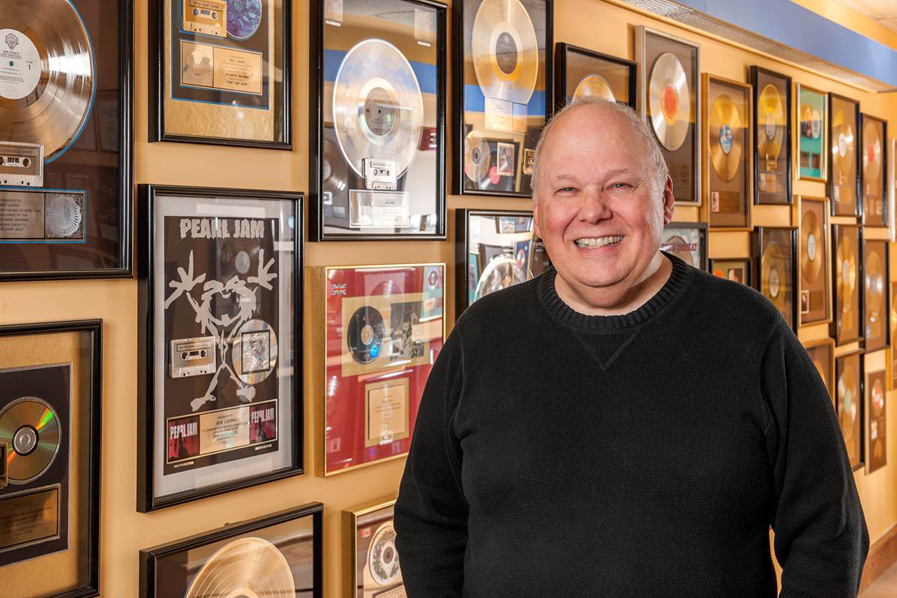

Starting at the Beginning with MQA Founder Bob Stuart

We start, logically enough, with Bob Stuart, the public face of MQA, one of the creators of the process, and founder of the company. During a lengthy Zoom call, Stuart discussed a wide range of topics including the mechanics of human sensory perception, psychoacoustics, digital recording, and the need for and benefits of the MQA process – as well as its future. Stuart began with a discussion of the history of Meridian’s involvement in digital audio, the development of Meridian Lossless Packing (MLP), and how that eventually led to MQA. I apologize for being unable to present more of the long, discursive conversation.

We inevitably go back to the “is MQA lossless?” question.

We’ve tried to answer this all the way around it, with Q&A with Stereophile, with Computer Audiophile…MQA cannot be lossless in the terms of a lossless codec, if you start with the digital, because we do a process before we package it—and the package we call ‘deblurring” That’s the simplest way of describing it. This is the process of changing from PCM to the B-spline sampling system. Why do we do that? We do that because it tightens the time domain, it removes ringing. Combined with other processes, it removes the noise modulation.

The simplistic way of understanding what’s happening there is that we’re not smearing every music detail in time, backwards and forwards. Otherwise, with a conventional system, you get hints of it before and hints after. You’ve seen the impulse responses.

We avoid that. And the consequence of that, when you listen to it – and again and again and again, in the studios, people say, “you’ve made it better” – we’ve made it clearer because we took digital hash out.

MQA, because it removes or cancels artifacts in the beginning, and then uses basically a lossless folding process, will never measure losslessly – if it’s working as it should, which is to de-blur. On the playback side, we’re also deblurring the time. The decoder and the renderer are taking out the ringing that the DAC’s trying to put back in.

When you say “deblurring,” that refers to improving the impulse response?

And the modulation noise. Those two things go together, because with digital you’re sampling, but you’re also quantizing into steps. Another area that people don’t understand unless they’re trained in digital audio, and have studied it deeply, is “what’s the difference between 16 and 24 bit, and what actually does the bit-depth mean”. Some would say, “let’s do 32”, or “why not 64?”

When you do more bits, two things are available. You get smaller steps. If you use dither, it doesn’t matter, because the steps are linearized. And if you have more bits, you can get a lower noise floor. The simple fact is, we don’t need the dynamic range of 24 bit, let alone 32 bit – because air doesn’t have that dynamic range. From the loudest sounds we can hear down to the silence of the planet – is about 19 bits.

It’s another area where data can be used unnecessarily, but also – there’s an advantage, when, as we have done, is to say, “let’s look at these recordings. Every recording – our encoder analyzes the noise floor. For example, I could play you a great-sounding Ella recording on analog tape – and the effective dynamic range is about 11 bits. We’re now approaching 20 million albums that we’ve encoded, worldwide, and we have statistics from all these recordings. The lowest noise-floor that we can find in a real recording, is 17 bits, in the band up to 20 kilohertz. These are specialist recordings, with minimal mixing and processing, from the usual suspects, labels like 2L.

Bit depth is another aspect that’s very hard to communicate to people…our encoder will capture the music, and transport that losslessly – not only losslessly, but with higher resolution, effectively, than the original, because we’re using the data effectively.

Were you surprised by the level of attention received by those [GoldenSound’s] Videos? They rather came out of nowhere, did they not?

Almost out of nowhere, because he gave us a week’s warning, he sent me an email saying, “I’ve done this, do you have any comments?” Well, you’ve seen the comments. I was just disappointed because I’d given a response saying, “look, this isn’t about a test.”

If you’d worked with any scientists, you’d know that if a scientist discovers a problem, they don’t publish, they go back and try to figure things out. I was very disappointed that it came out, for a number of reasons – obviously, it’s inaccurate, and it was also sensational, even though at the beginning he said, “I just want to be honest and unbiased” – all the language was not. All the language was the language of attack, from our point of view, including the title, “Is MQA Better Than FLAC?” – it’s an illogical question. MQA is content, FLAC’s the container. It’s like saying, “bottles are better than wine.” You and I both know the answer to that. (laughs)

I was disappointed for him also. And I was annoyed – who wouldn’t be?

Do you think that historically the way that MQA and you personally have responded to criticism has worked against you? You’ve rather been labeled bullies, through the years.

Maybe by a very small group. I would say we’ve had incredible patience…I think on some level we didn’t argue enough and were too polite and too British about it.

Looking back, would you have handled the events at RMAF differently? [Ed.: Bill’s question is a reference to a video of an ugly exchange during an presentation at a past Rocky Mountain Audio Fair that touched on MQA where MQA executives in the audience argued with the presenter about his material.]

The problem with Rocky Mountain is that there was never going to be a debate in the room because the people doing the presenting had made up their minds, they’d come in with a series of criticisms about MQA, like the logo, and others. Each one of these things we had answered, once, or twice, or several times already, and it fell on deaf ears. And so, I think it was very frustrating for our team…and quite a few people in the audience were becoming irritated on our behalf.

I wasn’t at Rocky Mountain. If I’d been there, would it have been different? Maybe. Because I might’ve walked up to the front, taken the whiteboard, and said, “here’s the answer to that question – AGAIN.” Because I’d answered the questions again and again and again….

Many of the people involved in the controversy – and I’m not being dismissive – they don’t read much. They read to the end – and if you write something down and explain it all, there are two problems you’re going to get. One is that you’re accused of being long and boring – or you’re accused of using marketing-speak because you’re trying to simplify and bring it up to the level where the average intelligent 10-year-old can understand the problem….

Would we do that differently? Yeah, we wouldn’t have gone.

Thanks for your time. It was a pleasure talking with you.

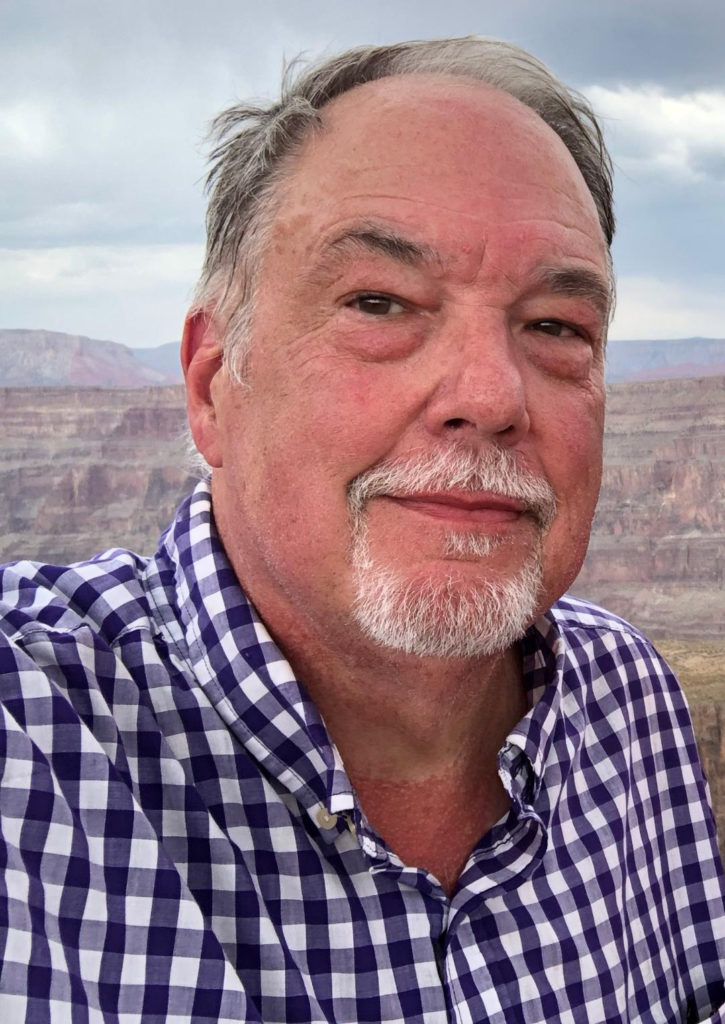

Grammy Award Winning Mastering Engineer Bob Ludwig on MQA

Grammy Award winner Bob Ludwig is perhaps the best-known mastering engineer in the world. All recorded music is mastered before its release, whether it’s a digital file, an LP – or even a cassette. The process of mastering is as much an art as it is a science – which of course is true of producing and recording music in general. The skill-set of the mastering engineer, however, is highly specialized, devoted to compensating for the requirements and peculiarities of the delivery medium used, so as to enable the presentation of the recording in as close to its original form as possible.

In the audiophile world, Ludwig’s name (or that of his company Gateway Mastering) on a recording’s label is solid gold, a guarantee of pristine, dynamic sound. Ludwig speaks in this video about what MQA does for his mastering projects, emphasizing the importance of the authentication process. The video was produced by MQA, so it is, as one would expect, supportive of the process. Ludwig says, “MQA has many facets”, and he goes on to explain aspects of the process that are often criticized as being vaguely-defined, such as “deblurring”. The video is a valuable aid in understanding the claims and aims of the MQA process, and what occurs during its implementation. The viewer may be left with the sense of, “why didn’t they say that in the first place?”

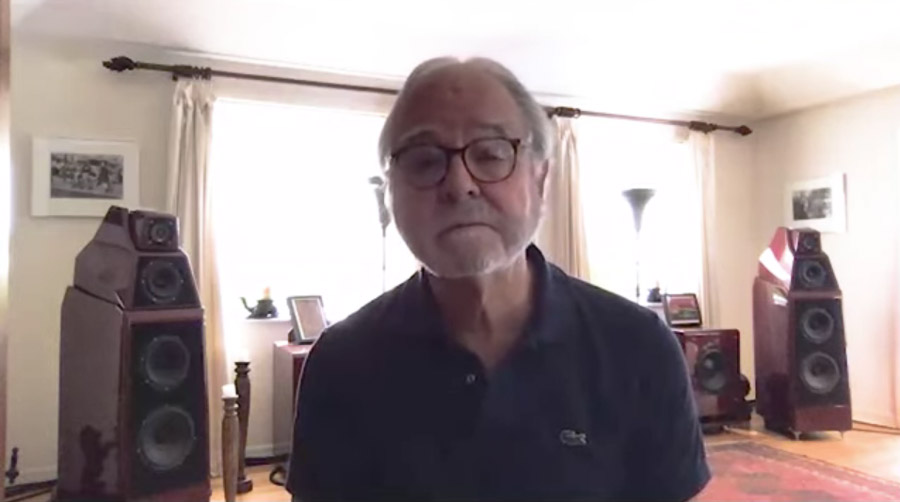

Engineer George Massenburg, Grammy Winner & Ardent Believer in MQA

George Massenburg is also a mastering engineer, in addition to being a recording engineer, inventor, professor at McGill University and lecturer at several other schools. He’s recorded many well-known artists including Little Feat, Linda Ronstadt, Randy Newman, Billy Joel, and dozens of others; like Ludwig, he is also a Grammy winner. He is also an ardent believer in the benefits of MQA. Massenberg is a polymath with expertise in several fields, as well as being an engaging storyteller. Sticking merely to the subject of MQA during a Zoom call was difficult, but here are the main points on the topic – part monologue, part Q&A. As is true of most conversations, it winds around, rambles, and changes directions at times:

Tell me how you got started with MQA, and what it brings to your work.

I’ve been carrying a banner for high-resolution audio for as long as I can remember, and have been appalled and disappointed by digital audio since its inception. I listened to the first digital audio, the Soundstream system, in the late ‘70s. It was interesting; you could do all sorts of things with it, and that attracted me. The idea of some kind of permanence, it turns out, is pretty chimerical, but it was interesting at the time.

Between that and the introduction of CD – which was and is a dreadful platform – and fighting the fight to understand why it didn’t sound very good, has been my life’s work.

So one of the things we wanted to do early on was to get sample rates up. It’s been a long, and sometimes lonely fight…I’m a developer, kind of an inventor. The thing I can tell you over the years is that coming up with a great idea is pretty easy. [Designing and building my equalizer] wasn’t the great effort; the great effort was selling it to people who didn’t understand it and weren’t listening.

And that continues. People that want a simple answer don’t understand quality, don’t listen. MQA is underscoring that idea that you really have to love music and love listening to music to even start to understand what it does.

My first conversation with Bob Stuart was all about “lossless.” We were looking for a definition, through the Recording Academy, for “high resolution.” The industry originally said that “high resolution” was 48/24, and I fought that. I thought you needed to get the sample rate up, at least in production.

I talked to Bob, listened to what he had to say, and it made more and more sense, The three things [MQA] does is provide authentication – a subject which has been a nightmare for me because people would remix my work, remaster my work, “improve” my work…and it’s CRAP! It’s all crap. This is a step in the right direction, correcting artist’s and creator’s intent.

Secondly, the idea of being able to better use the data space – 96/24 data space, even more so, the 192/24 data space goes pretty much unused in the idea that you have to have lossless audio to 24 bits. There’s no such thing as audio beyond about 21 bits in A/Ds and D/As. You run into thermal noise; you run into the fact that not much music really happens at 90 kHz, certainly not at full level – why not reuse the space?

This is where Peter Craven’s idea of – and I’m not keen on the term, but I’ll use it because it’s unique – origami, weaving the data space so that you can fit wideband, high-resolution audio into a 48/24 data space.

The third thing MQA does – and this is one of the most important things we’ve done in digital audio, even though it’s not unique to MQA – is to attempt to correct the D/A and A/D converters for artifacts. What it does with D/As is to take an impulse response and reshape it before it goes to the D/A. This final step of MQA is intimately tied to the response of the D/A. That’s been very good in correcting long-known problems with D/As. It’s not unique to MQA, but it does it particularly well.

So, all of these things put together—to me, give me some hope [for digital audio] and the fact that I listen and want to be immersed in a musical work, gives me an advantage, as I really, really love that connection to music on a visceral level. And I’ve been denied that by 40 years of wrangling digital audio, trying to squeeze better performance out of it. MQA, to me, sounds like a big step forward. A very big step forward.

How do you actually apply MQA to your recording work? My understanding is that there are no MQA plug-ins for workstations? Is that correct?

That’s INCORRECT! [laughs] We have this plug-in called the MQA Pro Emulator, I use it in Pro Tools, and out of Pro Tools it gives me an MQA signal that goes into the D/A, is detected as MQA, I’m listening to an MQA process, and it allows me to adjust coefficients that I later upload to the server when I want to do the final transcode or final output of my digital files. I have a 96/24 mix that I’m working on, I’ll monitor it with the MQA Pro Emulator, and I’ll upload it to AWS for MQA processing.

So you can listen to what it’s doing on the fly?

Yes. My students and I have noticed that you make different choices in mixing when monitoring with MQA…this goes back to how we listen. Most of what you hear that [MQA] is a fraud, and that Bob Stuart is a charlatan, and it’s a ripoff – are from people that try to do the simple A-B tests. That’s all bullshit. A-B tests do not work for listening to music. They DO. NOT. WORK.

None of my deeper, more detailed work has been done using A-B listening. Digital audio is different. Early on, when the hue and cry went up about how bad CDs were, it was because we lost that immersive feeling of our analog recordings. We had 100+ years to get analog right, we weren’t going to get digital right in 10 minutes….

I’m hoping that if we have preferential, blind tests of a lot of people, they will reveal that people can listen longer, with less fatigue, to better audio. This is particularly important for mixing engineers, because we as a class have been doing a lot of damage to music, over the last 40 years.

Do you always listen with MQA?

If I have my choice, I’ll listen to music on Tidal, which generally has MQA classical. There are more and more sites [featuring hi-res] as there are more and more people who say, “look, I’m not lying to you, I HEAR it, I’m sorry that you don’t, maybe in time you will – but I don’t CARE if you don’t. Just get out of my fuckin’ way.” (laughs)

Massenburg repeatedly asserted that MQA-encoded digital audio allowed a more immersive, more relaxed, more visceral listening experience…intermixed with stories of Little Feat, Steve Cropper, and how Franklin, Tennessee, where many musicians and producers live, is a digital backwater. Massenberg left the discussion with a statement that “where losslessness is important is in the ANALOG domain” – the meaning of which is unclear, and will require further exploration and discussion.

Grammy Award Winning Producer Morten Lindberg of 2L

Morten Lindberg of the Norwegian label 2L was a Grammy Award winner this year for Best Immersive Audio Album and was also nominated for Producer of the Year, Classical. Lindberg’s minimalist, precise recordings are audiophile favorites, and he is an ardent supporter of MQA. He expressed willingness to be interviewed for this article, but an intense recording schedule prevented him from doing so in time for publication.

Lindberg explains his experiences with MQA in another video from MQA:

Peter McGrath, Classical Recording Engineer & Former High-End Audio Dealer

Peter McGrath is a recording engineer whose purist recordings of classical music for the Audiofon and Harmonia Mundi labels and NPR are highly regarded. Unusually, he is also a former dealer of high-end audio gear and has been a brand ambassador for Wilson Audio speakers for over 20 years, demonstrating their products using his own recordings. He also is an enthusiastic supporter of MQA and has had a number of his master recordings processed with MQA. McGrath’s comments are taken from a lengthy email, and are excerpted with his permission:

“I believe that when MQA is applied to a well-made digital recording, that recording becomes something even more beautiful in terms of sound quality when listened to on a good quality playback system. What MQA simply CANNOT DO is make a badly mixed and highly processed recording (usually multi miked, multitracked, equalized, compressed, horribly over-processed recording…digital or analog) sound significantly better than without it. What I think that a lot of people involved in the debate about MQA overlook is simply the fact that one has to listen to it with a well-made digital file that has NOT been converted, to the same file that has [been converted].”

McGrath recounts the experience of first hearing his recording of pianist Zlata Cochieva, processed in MQA:

“This was a solo piano recital which I recorded with my usual high resolution set up at 88.2/24 bit. Only two mics and NO digital processing of any kind was applied to the recording. This file was representative of the best I had done recently…. I first heard my original file which did indeed sound very good…dynamic, clear, with tremendous articulation and detail….much of what I had recorded. Then he [Bob Stuart] played the MQA version. I finally heard for the first time in digital the actual sound of the true hammer impact on the piano strings that I captured consistently on my 30IPS analog recordings of years ago, and thought I would never hear again in the digital world… Since then I have had countless of my digital master files converted to MQA and in every instance, there has been an audible improvement in the sound quality that resembles more closely the original sound that came from the original analog microphone source. In essence, what MQA does for me is minimize the artifacts of the actual digitization process…both the A to D and the D to A.”

On playing his original non-MQA recordings, followed by the MQA version for a conductor friend, , McGrath writes: “I played a few moments of the non-MQA version, and he thought it was great. Then came the MQA and he was astonished at the difference. [He] said that the recording became much more like a genuine musical experience, and more akin to the sound he heard on the podium. More beautiful and real. I told him that there are a lot of people in the audio world who are opposed to the technology he had just experienced, and his response to me was that it’s likely their objections are based on ignorance, or a possible lack of a concert hall experience.”

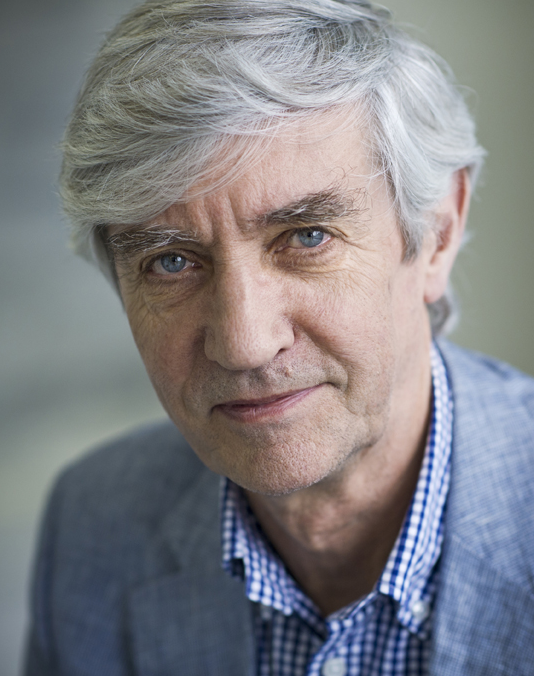

Stereophile Magazine’s Jim Austin, ‘As We See It’

Jim Austin is Editor of Stereophile magazine, holds a Ph.D. in Physics, and was a Senior Editor at Science magazine. The audio world loves titles, both real and assumed; refreshingly, Austin does not refer to himself as “Doctor”.

His As We See It editorial in a recent issue of Stereophile was entitled, “MQA again”. In that column, Austin does not directly support MQA, but does so indirectly by pointing out what he views as deficiencies in GoldenSound’s test methodology. The opening is provocative, and reflects the controversy and antipathy that have followed MQA from its beginnings: “MQA has once again floated to the surface of the perfectionist-audio pond—not belly-up as some have hoped but forced there by relentless pursuit by anti-MQA predators posing as impartial jellyfish.”

He continues, “I am not a partisan, for or against MQA. If I’m partial to anything, it’s fairness, and GoldenSound’s critique is unfair. MQA isn’t perfect, but here it has been falsely maligned.”

Austin goes on to contend that the test signals utilized by GoldenSound result in aberrant output, simply because they are forcing the program to process signals that MQA was never intended to process. He concludes,

What GoldenSound’s tests show, then, is that a bull in the china shop can damage the china. The solution is not to throw out the china but to keep out the bull. GoldenSound’s tests are a missed opportunity.”

Stereophile, As We See It, ‘MQA Again’

Next Week: Part 4 Conclusion

In our next, last and final installment, we’ll review all that has passed.

A Bill Leebens Guest Post

Bill Leebens has been a published writer since the age of 15 and has worked in audio since he was 16. He edited Copper magazine while at PS Audio and has also worked in automobile racing, medical imaging, and even as an IRS tax examiner. Bill lives in Colorado with two impatient dogs and several very patient humans.

Reach Bill at: bill@leebensllc.com

Bill’s interview with Bob Stuart was 2 hours and this is the total summation of that interview? Is more forthcoming? Kind of unsatisfying after the hype yes?

Hi Fielding,

As the article was running long and we wanted to get in a range of voices, we edited it down to the core issues surrounding the controversy – the subject of this series.

Ted

About that quote you referenced: “This whole argument demonstrates the reason this industry will never get bigger (‘this industry’ meaning high-end audio).”

That quote applies directly to technologies like MQA.

I don’t hear what those engineers heard. I’m neither here nor there with MQA’s sound. However, this industry will never grow until it makes high-resolution music easy, ubiquitous, and automatic.

Look around your neighborhood, and count how many neighbors are clamoring to buy (or have bought) a system that requires additional gear to play songs they’re already playing from a streaming service they already subscribe to, a system that must do a software “first unfold” and a hardware “final unfold” to give you what other services already give you without all of the above.

Yes, we hardcore audiophiles like to buy and manipulate extra gadgets, but that’s no way to grow our beloved pastime among civilians.

BING BING BING BING winner winner chicken dinner!

Years ago at a presentation on “The future of audio” at RMAF, I made the comment that, “the next time some old fat idiot like me bitches about the iPod, rather than recognizing it as the greatest single marketing opporrtunity the audio industry has ever received, I’m gonna punch him in the face.”

Update “iPod” to Sonos or whatever—nothing’s changed.

It is hugely frustrating. I’ve heard a number of manufacturers talk about producing “high-end Sonos”—but where is it?

And btw, I hate extra gadgets…but I’m the exception to the audiophile rule. As usual. ;->

Thanks for your insightful comment.

This conversation made sense 10 years ago. Today, it’s moot. With FLAC and other high-rez formats now easily streamable, who needs an encode-decode overlay? I don’t. And virtually all of the major streaming sites have abandoned it (MQA).

Ted lets go back to is MQA a marketing scam? Here are some factors that would indicate a MQA is marketing scam.

1. Financial pressure such as operating losses and negative equity.

2. Confidentiality agreements to examine the product or use it commercially.

3. Pressuring manufactures, with tactics like time is of the essence and if you do not sign early licensing prices will rise. The audio press adding pressure by reporting on MQA availability of products without music to listen to MQA.

4. Preannouncements and press coverage two years before it was possible for a consumer use the product.

5. It doesn’t work well with the way most modern music is recorded, e.g., laying down tracks, mixing, equalization, compression and other processing.

Another nice video about pressure on manufacturers about filters and some analysis by GoldenOne. On the Vaporware thread of course.